Indice

- Project Sketch and Plan

- The Mortises

- The Tenons

- Half-Lap Joints

- Moulding the Side Frame Uprights

- Dry Fit Assembly

- Completing the Two Side Panels

- Completing the Frame

- Bottom Guides for the Drawers

- Top Guides for the Drawers

- Building the Drawers

- Preparing the Drawer Fronts

- Installing Drawer Stops

- Drawer Test

- Building the Cabinet Doors

- Rounding the Frame

- Fitting the Hinges

- Assembling and Fitting the Doors

- Preparing the Lower Shelves of the Sideboard

- Finishing the Sideboard

- Installing the Door Catch System

- Creating and Installing the Internal Shelves

- Making the Top Panel

- Making the Lower Plinth

- Fixing the Plinth

- Final Look of the Sideboard

- Note on the Wood Staining and Finishing Process

If you love rustic and natural style, you'll enjoy discovering how to make a sideboard in the “arte povera” style using chestnut wood — a sturdy, warm and versatile material that’s relatively easy to find and won’t break the bank. It's perfect for creating charming, high-quality furniture with character.

In this article, I share the wonderful work of Mariobrossh, a passionate DIY enthusiast (and a true woodcraft artist) who built his own chestnut wood sideboard and documented each stage of the process. He also included some simple yet incredibly useful tips along the way.

So, read on if you’re curious to see how a few planks of wood can become a handmade masterpiece in the best “arte povera” tradition.

Project Sketch and Plan

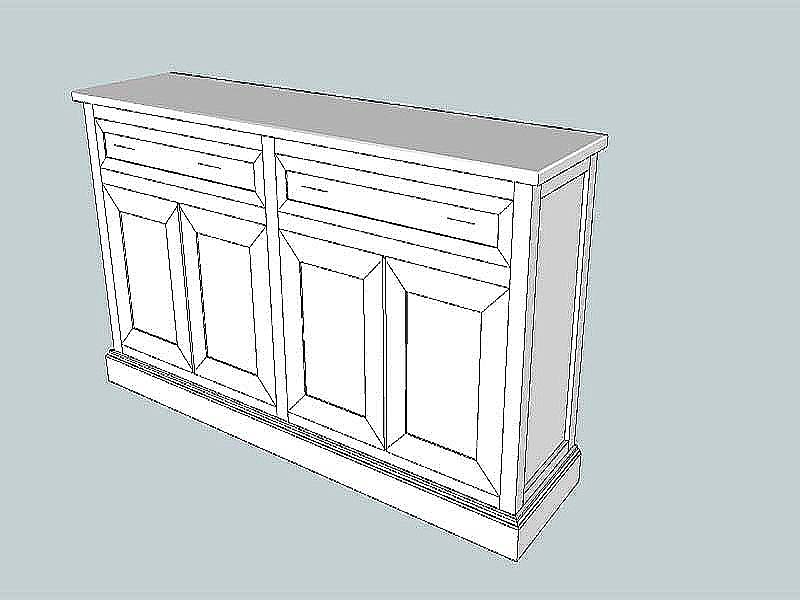

I started building this sideboard — which measures 180 x 98 x 42 cm (yes, I admit I may have gone a bit overboard!) — using 5 cm thick chestnut wood beams for the main structure. As always, I prepared a sketch to calculate the individual pieces I’d need to cut and to get a general idea of what the finished piece would look like. The sideboard should turn out something like this:

The Mortises

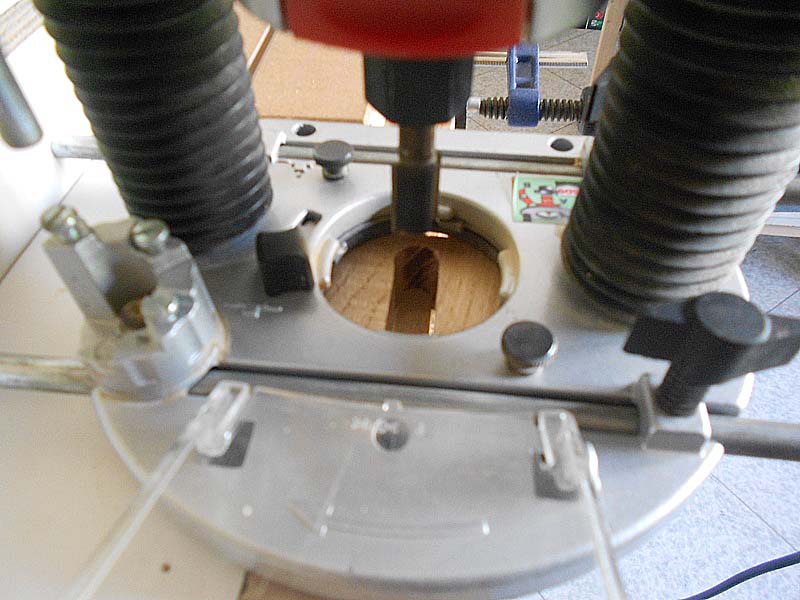

For assembling the frame — which, as mentioned, is made from 5 cm thick chestnut wood beams — I went with traditional mortise and tenon joints. To create the mortises, I used a homemade jig that helped me speed things up a bit.

Tip: If you’re interested in making your own jig for cutting mortises more quickly and consistently, check out this article where I explain how to build one: Building a Wooden Jig to Create Precise Mortises Using a Vertical Router (by Capitan Farloc)

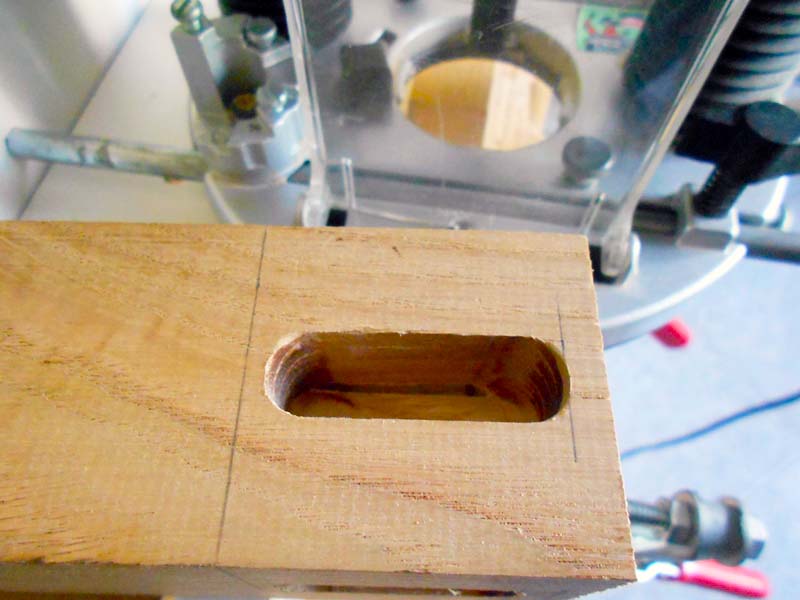

This was the result of a test run I did on a scrap piece of wood before starting the full batch.

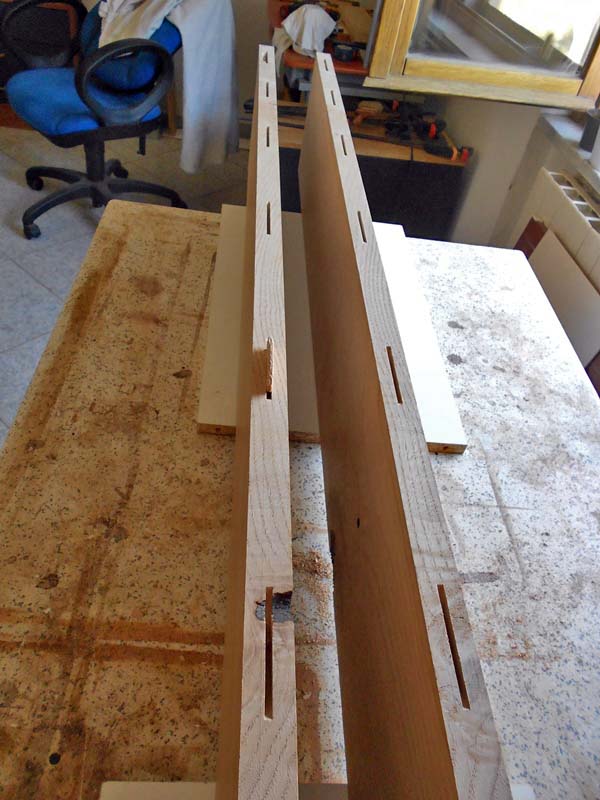

The Tenons

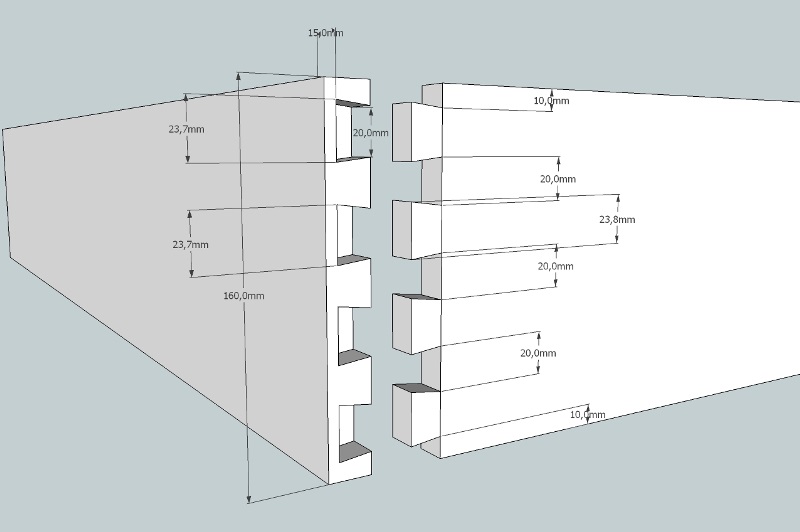

To make the tenons, I used a vertical router fitted with a straight bit — the same one I used for the mortises — to cut the grooves. To speed things up, I clamped several pieces together so I could cut them in batches. It’s worth noting that next to the workpieces I added two scrap bits of wood (called “sacrificial pieces”) onto which I screwed a guide. This guide serves a dual purpose: it keeps the router straight and helps control the depth of the tenon.

Here's the final photo of the tenons cut into the chestnut beams.

Half-Lap Joints

Unlike what I’d planned in the original project sketch, I decided to leave the three front crosspieces whole to give the structure more strength. So, at the points where they meet the central frame, I used what are called half-lap joints (also known as half-thickness joints).

Moulding the Side Frame Uprights

I added moulding details to the uprights of the two side frames using a special bit mounted on my router. This helped give the sideboard a more elegant look and made the design feel less plain.

Dry Fit Assembly

At this stage, after testing each individual joint, I try assembling the frame “dry” (that is, without glue) to check for any imperfections and make adjustments where needed. It also helps to start getting a sense of how the sideboard will look as a whole. I use clamps to keep everything firmly in place and prevent the unglued pieces from coming apart.

This close-up shows the half-lap joints between the crosspieces and the central frame.

Completing the Two Side Panels

Once the frame is properly in place, I can move on to gluing — but only after finishing the side panels, which need to be closed off before being fixed to the frame. To do this, I cut grooves along the inside edges of the beams that make up the frame, and slot in a piece of plywood that’s been cut to size. Then I glue the pieces together and clamp them until the glue has fully dried.

The photo shows the right-hand panel, but the exact same process is repeated for the left one.

Completing the Frame

At this stage, I can start gluing together the frame — or “skeleton” — of the sideboard. I begin by attaching the first side panel to the crosspieces and the central frame. Once the glue has dried, I move on to the second side panel, completing the load-bearing structure of the piece.

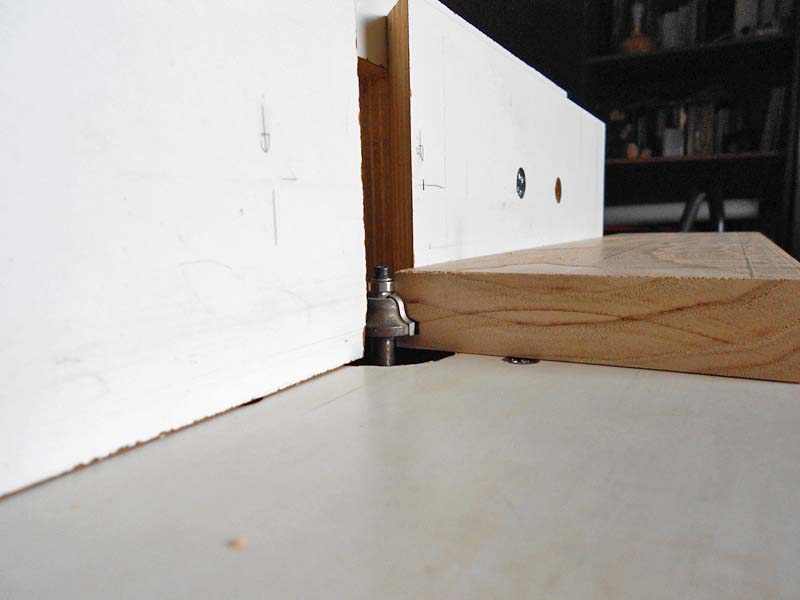

Bottom Guides for the Drawers

Rather than using side-mounted runners, I opted for bottom guides on which the drawers rest. These are paired with top guides that prevent the drawers from tipping forward when opened.

To make the guides, I used hardwood strips, which I then cut to size using the circular saw. I shaped them so they’d slot neatly into the panel structure, just as shown in the photo.

The guide is then glued in place and securely clamped to the rear upright until the glue has fully dried.

As for the front upright, I chose to add a support piece of wood and screw everything securely into place.

It's worth noting that the bottom guides are mounted a couple of millimetres higher than the crosspieces. This ensures that, when opening and closing, the drawer doesn’t rub against the crosspieces, which could wear them down or cause damage over time.

Top Guides for the Drawers

As I mentioned earlier, choosing bottom-mounted guides for the drawers also meant I needed to add top guides to keep the drawers level when opening and to prevent them from tipping forward due to their weight.

In this photo, you can see how I installed the top guides, which I made from a few wooden strips.

Building the Drawers

At first, I was planning to use dovetail joints for the drawers, and I had even drawn up a properly dimensioned diagram for the cut-outs.

After several attempts — which proved quite tricky and didn’t give the results I was hoping for — I decided to assemble the drawers using a groove to slot in the back panel.

Basically, after cutting grooves into the sides of the drawer with the router table for the bottom panel, I made a second, wider groove at the back to house the rear panel.

The photo makes it all much clearer.

This photo shows the detail of the joint between the drawer sides and the back panel.

It’s worth noting that the groove at the back of the drawer runs all the way to meet the grooves for the bottom panel. This allows the panel to extend slightly and be screwed to the underside of the back of the drawer, preventing it from sagging under the weight of stored items.

This setup also makes it easy to replace the bottom panel later on — simply unscrew it and slide it out from the back.

In this photo, you can see the overall assembly of the drawer, including the screws securing the bottom panel to the back.

At this point, I tested the drawer sliding into its slot — and everything works perfectly.

Preparing the Drawer Fronts

As you can see from the lighter colour, the drawer bodies are made using more affordable wood (such as pine or fir), while the fronts — which remain visible on the finished piece — are made from chestnut wood.

Once the fronts are cut to size, I use the router table to make the side recesses that allow them to slot into the drawer sides.

This detail shows how the drawer front slots into the drawer side.

Installing Drawer Stops

Once the finished drawer is placed into its slot, it’s important to prevent it from sliding too far back into the unit. After positioning it so that the drawer front sits flush with the rest of the frame, I glue small wooden strips onto the side frames — between the upper and lower guides. These act as end stops, making contact with the sides of the drawer and preventing it from going in too far.

Drawer Test

At this point, all that’s left is to slide the drawer into place and check that it sits flush with the rest of the unit. As you can see in the photos, the result is spot on.

Building the Cabinet Doors

To make the cabinet doors, I built a frame using chestnut wood, cutting the boards at 45 degrees with the table saw. In the photo, you can see how I added a support block to the 45-degree mitre guide on the saw — this helped hold each piece in place and ensured that all the cuts came out exactly the same.

Rounding the Frame

Next, using the router table, I round off the inner edges of both the uprights and the crosspieces. After that, I cut the groove where the plywood panel — which will serve as the door’s central panel — will be slotted in.

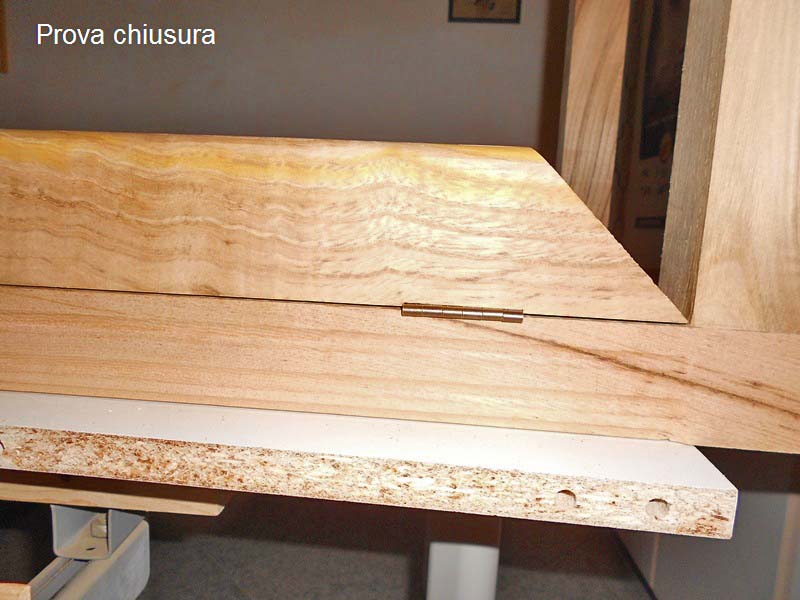

Fitting the Hinges

Each door needs two butt hinges mounted on one of its uprights, and these require recesses so that the hinges sit flush with the wood surface. Since there are two hinges per door, four doors, plus the matching recesses on the cabinet frame — that’s a total of 16 hinges and 32 mortises. That’s exactly why I made a simple jig using three offcuts of wood, as shown in the next photo.

The jig was designed to rout out the hinge recesses using a handheld router fitted with what’s known as a guide bush (or template guide), which typically comes standard with most routers or can be purchased separately.

The guide bush rides along the inside of the jig (which, of course, must be slightly larger than the actual recess to be cut), allowing for a repeatable, accurate process with no risk of error.

The next photo shows how it works in practice.

After routing (naturally setting the depth stop on the router to match the 2 mm thickness of the hinge), the result looks like this.

I then test the fit to make sure the hinge slots properly into the recess I’ve just routed.

To cut the hinge recesses on the cabinet uprights, I drill two holes in the jig. This allows me to use clamps to secure it more easily to the upright.

With all the recesses routed, I test-fit the hinges to make sure the doors close properly and that the hinges sit flush without creating any gaps. The test seems to have gone well.

Assembling and Fitting the Doors

At this stage, the doors can be assembled by inserting the plywood panel and gluing the frame pieces together.

Like the side panels, the door panels appear lighter in colour because they’re made of poplar rather than chestnut plywood, which I couldn’t get hold of. As a result, the stain will be absorbed a little differently. However, with careful adjustment of the stain mixture, it’s still possible to achieve a matching tone.

Once everything has dried and the doors have been fitted to the sideboard, this is how the piece now looks.

Preparing the Lower Shelves of the Sideboard

Since I had some offcuts of 4 mm plywood and a few fir battens, I decided to make the two lower shelves (left and right) using a sort of simplified hollow-core panel: simple – inexpensive – sturdy. Technically, it’s missing the bottom face you’d find in a proper hollow-core panel, but as it will sit underneath, I figured I could do without. Here are the photos.

P.S. I used an electric stapler to fix the frame — quick and easy to use.

Once the frame is finished, the plywood panel is glued on top. The panel is cut slightly larger than the frame so it overhangs on all sides. Then, using a flush-trim bit on the router, I trim it back level with the frame — that way, there’s no risk of cutting it too small.

Once everything has dried and been trimmed, I do a test fitting — and everything lines up perfectly.

Finishing the Sideboard

For the finish, I first applied a wood stain from Veleca. Then I used a water-based pore filler as a base coat, followed by a water-based topcoat with a wax-effect finish — and this is the final result.

Now all that’s left is the top and the base. At first glance, it has quite a country or rustic look — which I really like — but I’m hoping that with a moulded base it will take on a more classic appearance.

Installing the Door Catch System

For closing the cabinet doors, I chose to use simple (and inexpensive) magnetic catches. As shown in the photo, I mounted them onto the rail above the doors so they’re slightly hidden from view.

Creating and Installing the Internal Shelves

The shelves were made from 18 mm melamine-coated plywood and finished with pre-glued edging.

Once I had decided on the height for the shelves, I marked out the position for the shelf supports. To ensure the holes were all at the same height and the same distance from the edge, I used a piece of plywood with a hole drilled at the correct height to serve as a jig.

Using the hole in the jig as a guide, I marked the points with an awl, then drilled the holes to mount the shelf supports.

Once the pilot holes for the screws were drilled, I fitted the shelf supports. I always use the type shown in the photo because not only do they provide solid support, but they also stop the shelf from shifting and help brace the sides of the cabinet — preventing them from wobbling. This is especially useful (though not the case here) when fitting shelves into bookcases without a back panel.

These shelf supports are a bit different from the usual type where the shelf simply rests on top — they require holes to be drilled in the shelf itself so the supports can slot in. To mark the exact position for the holes, just place the shelf carefully on the supports and tap lightly with a rubber mallet at the contact points.

With the holes drilled in the shelf, all that’s left is to slot it onto the support pins — and that’s it, job done.

Making the Top Panel

To create the top panel, the first step was to cut thick boards — around 3 cm thick — from a large chestnut plank. This is a job that’s not really feasible with regular hobbyist equipment, so I had a carpenter friend do it for me. That said, it’s also possible to buy chestnut boards in the desired thickness from timber merchants, who will often cut them to size on request.

To join the boards edge to edge and create a wider top, I used a biscuit joiner to make a series of slots along the edges to be joined.

With the biscuits in place and the glue applied, I joined the boards and clamped them together using woodworking clamps until fully dry.

After removing the clamps, I sanded the surface using a random orbital sander — first with 80-grit sandpaper, then with 120-grit — to achieve a perfectly smooth finish.

As seen in the photo, once the surface was dampened, the beautiful grain of the chestnut trunk emerged right along the join between the two halves of the top.

I then routed the edges to round them off, and followed up with the same finishing process used on the rest of the cabinet: first staining the wood, then applying the usual water-based base coat and topcoat.

Making the Lower Plinth

To make the plinth, I once again used 3 cm thick boards. For the moulding, since I didn’t have a router bit large enough to match the full thickness of the board, I created the profile in two passes. In the following photo, you can see the result of the first pass.

Then, by lowering the router bit, I was able to make the second pass and complete the moulding profile.

I cut the pieces to size with 45-degree mitre joints and did a dry fit — not bad at all!

Fixing the Plinth

After applying the usual wood finish, I fitted the plinth.

As shown in the photos, I opted to mount it with magnets rather than gluing or screwing it in place — mainly so it can be easily removed when my wife wants to clean underneath the sideboard.

Final Look of the Sideboard

Questo è come appare la credenza dopo averla terminata. Come dicevo aggiungere il piano superiore stondato e lo zoccolo con la modanatura ha contribuito a dare alla credenza un aspetto più classico.

Note on the Wood Staining and Finishing Process

The final colour of this sideboard is the result of many tests and a lot of patience. There are several ways to stain wood: you can buy ready-made stains (for example, Sayerlack has an entire range called the "Linea Blu"), or you can purchase dry pigments (mordants) to dilute, or — as in my case — use a concentrated liquid product such as Veleca's Tingilegno. It's a water-dilutable liquid available in various tones. The more product you add, the darker the resulting stain.

Generally speaking, the final colour — after the full finishing cycle — ends up being similar to how it looks when the stain is first applied. Once dry, the tone lightens slightly, but the topcoat brings it back to a deeper shade.

My process is as follows:

- Sand the wood with progressively finer grits: 80 → 120 → 240 → 400

- Wipe the surface with a damp cloth — to raise the grain and remove dust

- Once fully dry, give it a quick final sanding with 400 grit and clean off the dust with a dry cloth or compressed air

- Apply the stain using a very soft brush, working with the grain; the application must be smooth and quick, followed by wiping with a clean cloth to even out the colour

- After 24 hours, lightly sand again with 400 grit or 0000-grade steel wool, especially on corners and edges, where the stain may lift more easily

- Apply one coat of pore filler (turapori)

- Once dry, sand again with 400 grit and clean off the dust

- Now check the surface by touch — if it feels silky (depends on the wood), proceed to the topcoat; otherwise, apply another coat of pore filler

- The finish, whether glossy or satin depending on personal taste, should be applied with long, light strokes, always following the grain, without going back over areas already coated — ideally working against the light

Personally, I prefer water-based products (as they’re better suited for enclosed spaces), but for a more impact- and scratch-resistant surface, polyurethane products are the better choice.

Thank you for reading,

Mariobrossh