Indice

- Introduction

- Digital Multimeter: What It Is and How It Works

- Basics of the Digital Multimeter

- How to Measure Voltage

- Measuring Direct Current Voltage

- Measuring Alternating Current Voltage

- How to Measure Resistance

- How to Measure Current in a Direct Current Circuit

- How to Measure Current in an Alternating Current Circuit

- How to Use the Measurements Taken with a Digital Multimeter

- How to Use Ohm’s Law Formulas

Just bought a digital multimeter (or maybe you’ve had one for years but never really used it)? Don’t worry — this guide will show you how to use a digital multimeter in a simple and practical way. Learn how to measure voltage, current, resistance, and test continuity. Whether you're checking a battery, a power supply, or an electrical circuit, a multimeter is an essential tool for any DIY enthusiast. With clear photos and step-by-step explanations, you'll quickly feel confident using it correctly and safely.

Introduction

This guide includes (reviewed and updated by me) the content written by our forum friend Cabestano in a PDF guide shared a few years ago on the forum. Those who wish to do so can download it via a link provided at the end of this article.

Before diving into the reading, however, I want to remind you that whenever measuring powered components, extreme caution must be taken to avoid contact with electricity, which is very dangerous and can be lethal. Furthermore, some devices (such as microwave ovens and old televisions) can retain a high accumulated charge even when unplugged, which can also be fatal. So, before opening a device you are uncertain about, make sure to seek help from someone more experienced to determine whether it is safe to open and how to do so securely.

With that said, I’ll leave you to read the manual, which I must say has been written in a simple yet comprehensive way, covering all the most important points.

Thank you all!

Luciano (Capitan Farloc)

Digital Multimeter: What It Is and How It Works

The digital multimeter is a tool used to measure the electrical quantities present in circuits.

It’s highly practical, and in recent years its price has become so affordable that every hobbyist should have one in their toolkit. It’s preferable to the needle-based (or analogue) tester because of its sturdiness and low sensitivity to impacts. Moreover, it cannot be compared to the “legendary” phase tester screwdriver when it comes to the range and precision of measurements.

Let’s now take a look at the basic measurements for the electrical hobbyist that can be carried out using a digital multimeter.

The main measurements that can be performed are as follows:

- VAC (Volts Alternating Current): This measures volts (the unit of voltage) in alternating current. Alternating current is simply the type of electricity we find in all household outlets.

- VDC (Volts Direct Current): This measures volts (the unit of voltage) in direct current. Direct current is what you’ll find in car batteries, the batteries of portable devices, or the output of power supplies and chargers for our devices. It’s identified by a positive and a negative pole.

- DCA (Direct Current Ampere): This measures amperes (the unit of current) in direct current. It’s useful for measuring, for example, how much current the motor in your child’s toy or your car’s electric window mechanism consumes.

- ACA (Alternate Current Ampere): This measures amperes (the unit of current) in alternating current and serves the same purpose as the DCA but for alternating current devices, like household appliances. However, this measurement is usually not available on very low-cost multimeters.

- Ω (Ohm): This measures ohms (the unit of resistance). It’s used to check, for instance, the continuity of an electrical cable, the resistance quality of an iron or a hairdryer, and many other things.

Basics of the Digital Multimeter

Using the previous illustration as a reference, let’s now see how to start using the multimeter.

At the bottom of the multimeter, we find three sockets for the test probe plugs:

- The first socket, located at the lowest position, is labeled COM (Common). This is where the black plug goes, serving as the negative terminal for all our measurements. It will remain in place for every type of measurement.

- The second socket is labeled V--Ω mA and is where the red plug is inserted. Through this plug, we can measure Volts in Direct Current and Alternating Current, Ohms for resistance, and Amperes within the lower measurement ranges—up to 200 mA on our multimeter. This will represent the positive terminal for our measurements.

- The third socket is labeled 10ADC, used for measuring higher current strengths in Direct Current, up to 10 Amperes.

The combination of the central dial position and the placement of the plugs at the bottom allows us to carry out a wide range of measurements useful for our repairs.

How to Measure Voltage

When we talk about voltage (for example, 230 Volts), it’s always understood that we’re referring to the potential difference between two points. Comparing voltage to a hydraulic circuit, it would correspond to pressure.

The voltage supplied by a generator is, within certain limits, fixed. The voltage present in household outlets is 230 Volts, a car battery provides 12 Volts, and an AA alkaline battery delivers a voltage of 1.5 Volts.

The presence of voltage determines the ability to power a device. By turning it on, we allow current to flow through it—essentially enabling the flow of electrons, which are responsible for the work performed by the device (light for a light bulb, movement for a motor, heat for an oven, etc.).

Now, let’s look at how to measure it, starting with a simple battery.

Measuring Direct Current Voltage

To measure a Direct Current (DC) Voltage, follow these steps:

- Insert the black plug into COM.

- Insert the red plug into V-Ω-mA.

- Turn the central dial to DCV, position 20, which means the maximum measurable voltage in this position is 20 Volts DC.

Now, place the red probe on the + terminal of the battery and the black probe on the - terminal, and read the voltage across the battery terminals.

In the example shown, a new AA battery is being measured, and the reading is 1.60 Volts. If, by mistake, the probes are inverted, nothing serious will happen. A – sign will appear on the left side of the display, indicating the reversed polarity.

A good rule of thumb for any measurement is to start with a higher range if you’re unsure of the value to be measured.

In the specific case of batteries, it’s usually difficult to determine the remaining charge with an open-circuit measurement. It’s therefore better to measure the battery’s voltage while it is in use, for instance, installed in a child’s toy. If a 1.5 Volt battery drops to 1.1–1.2 Volts under load, it can be assumed that the battery is nearly depleted.

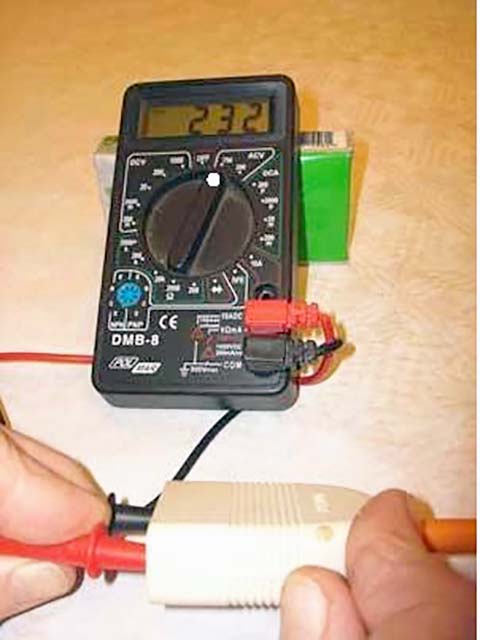

Measuring Alternating Current Voltage

The measurement of alternating current (AC) voltage is perhaps the most relevant for DIY enthusiasts, as it allows you to check for voltage presence in household outlets, extension cords, or verify the operation of devices.

To measure AC voltage, follow these steps:

- Insert the black plug into COM.

- Insert the red plug into V--Ω-mA.

- Turn the central dial to ACV, position 750, which means the maximum measurable voltage in this position is 750 Volts AC.

The probes can be inserted into the socket randomly, as there is no polarity to respect with AC voltage.

In the example shown, the voltage of an extension cord socket is being measured, and the reading is 232 Volts. Modern sockets, both mobile and fixed, often feature a safety mechanism designed to prevent children from inserting objects into the sockets, which could pose a danger to their safety (and ours).

This useful mechanism can sometimes make it difficult to insert the probes, requiring them to be inserted simultaneously and then rotated to find the correct reading position.

With the multimeter set to measure AC voltage, two other useful measurements can be performed, such as identifying the phase and neutral wires among the two conductors, provided there is a grounding system in place.

With the tool set as described above, place one probe in the central slot of the socket, then move the second probe to either of the lateral slots.

The slot that provides a reading of approximately 230 Volts will be the phase wire, while the other will be the neutral wire.

If neither slot provides a reading, the grounding wire in that socket is likely not connected.

If both measurements yield a reading of approximately 120 Volts, then it’s likely that the electrical system is older, where both poles are active phases.

How to Measure Resistance

Electrical resistance is, in simple terms, the property of materials to oppose the flow of electrons in an electrical circuit, thereby resisting the passage of current. Resistance is measured in Ω (Ohms), and the relationship between voltage, current, and resistance is defined by Ohm’s Law, a fundamental principle we’ll explore later. If we compare resistance to a hydraulic circuit, it would resemble the pipe's cross-sectional area.

One of the most well-known effects of resistance is heat generation, as seen in electric heaters, hairdryers, water heaters, etc. For home DIY purposes, it can be useful to measure the resistance of these devices to detect potential interruptions. Additionally, it can help identify breaks in an extension cord or even detect a short circuit (when wires touch each other where they shouldn’t).

Let’s now measure the continuity of an electrical wire: after stripping the insulation at both ends to expose some copper, set up the multimeter as follows:

- Insert the black plug into COM.

- Insert the red plug into V-Ω-mA.

- Turn the central dial to Ω, position 200. The multimeter will display the number 1 on the left side of the screen if the probes are not touching, indicating an open or interrupted circuit.

By placing the probes at the two stripped ends of the cable, the reading will instead show approximately 00.0 (the figure after the decimal point may vary slightly), confirming the continuity of the cable.

Using the same settings on the device, let’s check the resistance quality of an electrically heated curling brush (as shown in the attached photo). Touching the two pins of the device with the probes, the display initially shows the number 1. Next, increase the scale by turning the dial to Ω - 2000. The display will then read 734 Ω, which indicates that the internal resistance of the brush is intact.

Always remember that resistance measurements must be performed on devices that are not powered and disconnected from any other circuit!

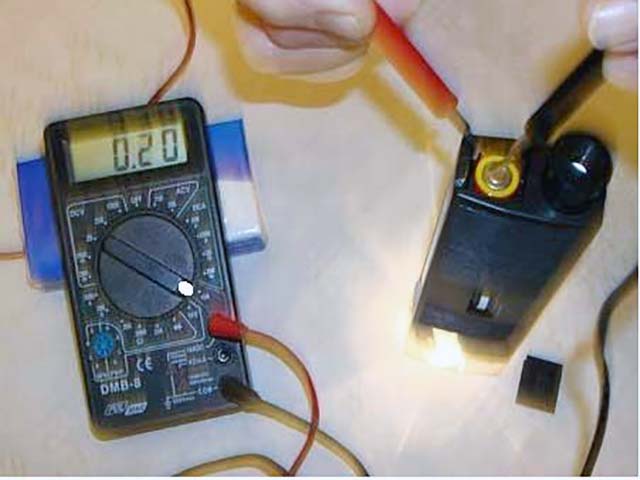

How to Measure Current in a Direct Current Circuit

Electric current is the flow of electrons that “powers” all our devices—heating our boiler, spinning the motor in our vacuum cleaner, and enabling hundreds of other applications. Its unit of measurement is the Ampere (A), and it is always measured in series with the circuit being tested. Compared to a hydraulic circuit, current can be likened to flow rate.

In the first example, we’ll measure the current drawn by a battery-powered toy microscope.

Remove the battery compartment cover and set the multimeter as follows:

- Insert the black plug into COM.

- Insert the red plug into 10 A DC.

- Turn the central dial to 10 A.

We start with the highest value because we have no idea how much current the lamp illuminating the viewer might draw. Place the black probe on the negative terminal of the battery (see photo) and the red probe on the contact that supplies power to the lamp. This way, the multimeter is in series with the circuit, and the reading on the multimeter is 0.20 A.

This means that the lamp requires 0.20 A at 3 V to function. At first glance, this may not seem very significant, but as you’ll see later, with a few calculations and some tricks based on the knowledge we’ve gained about measurements, we can arrive at more interesting results.

How to Measure Current in an Alternating Current Circuit

The current we just measured was from a battery, meaning it was direct current (DC). What about alternating current (AC)? Unfortunately, low-cost digital instruments typically do not have the capability to measure AC current. If you need to perform such measurements, you’ll need to invest in a more sophisticated (and more expensive) tool, although good digital multimeters can be found in the range of 30 to 40 euros.

For the connection example, I’ll refer to my old needle-based (analogue) instrument, which supports such measurements. Here too, the device whose current consumption we want to check must be connected in series with the instrument.

We’ll connect the electrically heated hairbrush we previously used to measure resistance in an earlier article. Power it on, and you’ll see it requires about 65 mA during operation. Let’s make a note of that—it will come in handy later.

I strongly recommend spending a little extra to purchase an instrument that can also measure AC current. Remember, these measurements are always performed under voltage, so exercise extreme caution while working!

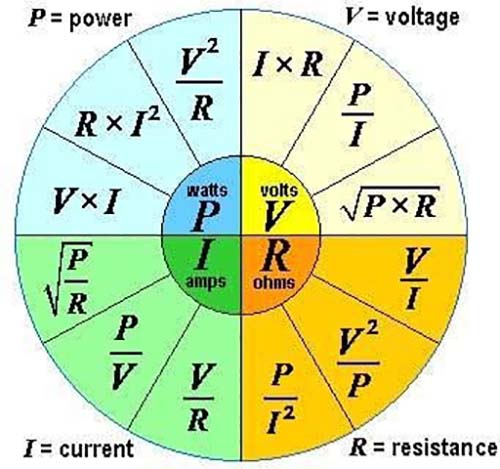

How to Use the Measurements Taken with a Digital Multimeter

In the previous chapters, we explored how to use the multimeter to carry out the key measurements of interest to DIY enthusiasts with limited knowledge of electrical engineering.

We’ve covered the measurement of Voltage "V" (in Volts), Resistance "R" (in Ω Ohms), and Current Intensity "I" (in A Amperes)—the fundamental measurements of electrical engineering.

The relationship between these quantities is governed by Ohm’s Law:

V = R x I

I = V / R

R = V / I

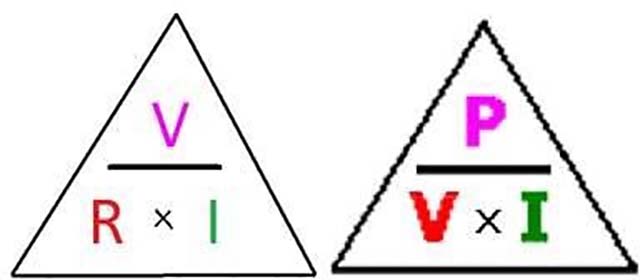

How to Use Ohm’s Law Formulas

Ohm’s Law tells us that there is a direct proportionality between voltage and current. Specifically, if the resistance remains constant, an increase in the voltage applied to the terminals of a device will result in an increase in the current flowing through it.

But let’s set aside the theoretical concepts, which you can explore further if you wish, and focus on finding a practical method for tackling small electrical DIY issues.

In this diagram, two triangles—often referred to as “magic triangles”—are shown. By covering the value you want to calculate with your finger, you can reveal the formula needed to find it.

For example, if you know the voltage of a device and its resistance, and you want to find the current ("I" for current intensity), simply cover the "I" with your finger. You will see that the operation needed to obtain this value is V / R, and so on.

In the second triangle, a new symbol appears: P, representing power in Watts. This helps determine the “power” required by a specific device. For instance, if we know that the resistance of our washing machine operates at 220 V and we’ve measured its current consumption as 10 A, and we want to calculate the power it consumes, we cover the P with our finger and see that the necessary operation is V * I. Therefore, our washing machine’s resistance will consume 2200 W. Similarly, if we know P and V and want to find I, we cover I and see that the operation required is P / V!

However, caution is needed because there are situations where calculations may not align perfectly with measurements. For instance, if we measure the resistance of an old incandescent or halogen bulb rated at 60 W, we might find a resistance of approximately 40Ω. Using all relevant calculations (V / R = I >> V * I = P), we notice the results don’t add up. The reason is simple: the filament of the bulb reaches temperatures of up to 2000 °C during operation, and its resistance changes significantly at that temperature!

This doesn’t occur with resistances that don’t reach very high temperatures, such as in washing machines or water heaters, where temperatures are moderated by water, or in hairdryers, where air acts as a moderating medium.

Everything discussed above applies to resistive circuits in both direct and alternating currents. However, it does not apply to motors, coils, or capacitors, which follow different laws that you can explore in any basic electrical engineering handbook.

As a bonus, I’m including a mention of the "formula wheel" diagram—it’s incredibly handy!

I hope you found the article helpful and interesting.

As promised, here’s the link to the PDF manual written in Italian by Cabestano: